Inverse perspective

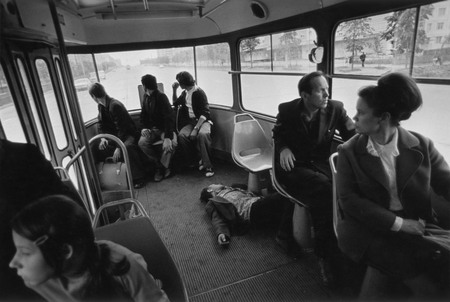

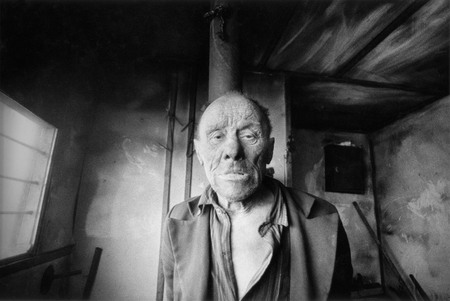

Valery Shchekoldin. Tatarstan, 1979. Gelatin silver print. МАММ collection

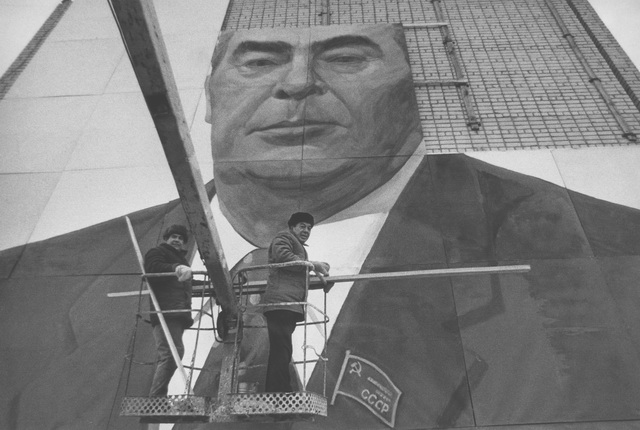

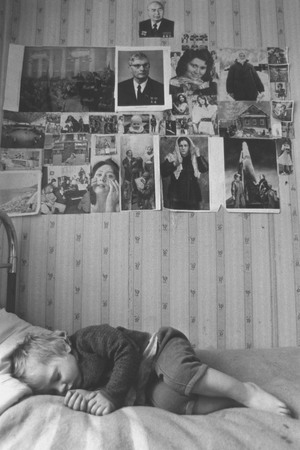

Valery Shchekoldin. Moscow, 1981. Gelatin silver print. МАММ collection

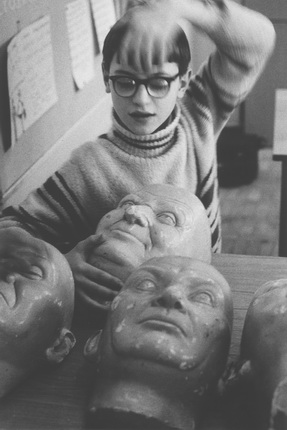

Valery Shchekoldin. Zagorsk boarding school for deaf, blind and mute children. 1983. Gelatin silver print. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Ulyanovsk, 1978. Gelatin silver print. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Dubosekovo, 8th of May 1984. Gelatin silver print. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Mari ASSR, Suslonger village. May 1, 1976. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Moscow region, Dubosekovo. May 8, 1984. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Moscow region, Dubosekovo. May 8, 1984. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Moscow region, Dubosekovo. May 8, 1984. МАММ collection

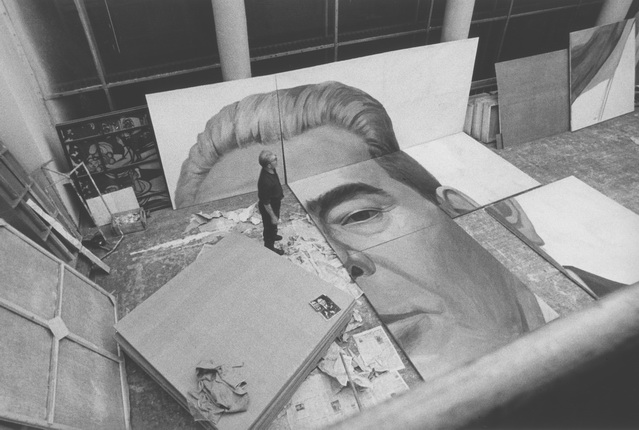

Valery Shchekoldin. Super blow-up. Ulyanovsk, 1978. Gelatin silver print. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Super blow-up. Ulyanovsk, 1978. Gelatin silver print. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Super blow-up. Ulyanovsk, 1978. Gelatin silver print. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Moscow. 1976. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Ulyanovsk. 1974. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Ulyanovsk region. 1979. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Ulyanovsk . 1979. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Ulyanovsk region. 1978. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Ulyanovsk. 1975. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Ulyanovsk. 1981. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Ulyanovsk region. 1974. МАММ collection

Valery Shchekoldin. Moscow. 1982. МАММ collection

Ulyanovsk, 26.09.2013—27.10.2013

exhibition is over

Memorial museum of Vladimir Lenin

Lenin Square, 1

www.leninmemory.ru

Share with friends

Artist’s collection, Moscow

Presented by the Museum “Moscow House of Photography”

Exhibition shedule

-

30.03.2010—25.04.2010

Moscow

Zourab Tsereteli Gallery of Fine-Arts

-

26.09.2013—27.10.2013

Ulyanovsk

Memorial museum of Vladimir Lenin

For the press

When you remember the distant past now lost from view everything seems larger, clearer and more meaningful than yesterday’s events that have yet to crystallise in time. Old photographs bring half-forgotten faces and long-past events closer. As you look at them you are instantly transported in the silver time machine to a moment recorded incidentally, by chance, and you experience it all over again. The past is seen from the present in reverse perspective: what once appeared insubstantial acquires definite meaning, what seemed important and indestructible turns to dust.

When I shot this series of photographs about our beloved visual agitprop and the primitive political disinformation that foolishly persisted even if nobody took it seriously, I understood that you have to see the humour there. I thought up a new tendency called’Sots-Cretinism’ (analogous with Sots-Realism, or Socialist Realism) and set out to reveal the absurdity of the system. The name first occurred thanks to my friend in Ulyanovsk who was a talented photographer and delightful human being, but remarkably uneducated. We used to show one another photographs and exchange opinions. In those days we had no criteria to judge photographs and no access to theoretical analysis on the subject, so we interrogated one another in an attempt to devise these criteria ourselves. One day my friend looked at a photograph that displeased him in some way, frowned as if he had terrible toothache, sighed and announced with regret:’Not enough idiocy.’ I couldn’t get him to expand on this statement. He couldn’t explain what he meant by ’idiocy’. Everybody laughed at him, they refused to take him seriously — surely there was more than enough idiocy in our lives already. But I thought his words should be interpreted literally, that photographs should indeed act as a concentration of the idiocy pervading our personal lives, our system and society. Most of all our system, since the system made idiots of us. As we all know, any idea can be reduced to absurdity. At the end of the Soviet era the propaganda machine churned out a vast amount of falsehood and absurdity that poisoned society and destroyed the state. The ordinary people viewed these demagogic slogans with disbelief, but tolerated them. The party leadership was in its dotage, the people drank to forget and the economy falling apart. Modernisation of the system was needed urgently. Andropov had begun the task and it was then tragically completed by Gorbachev.

When I had enough photographs for this series I pasted them in an album and envisaged publishing a book entitled’The Art of Degeneration’. But the Soviet regime was still in full swing: Brezhnev had only just died, Andropov was still alive — there was no thaw in sight and on the contrary, the system seemed set to tighten screws. Who knew what would happen if Andropov still had a few years to live. So I viewed the book with a touch of humour too, and meanwhile went on collecting material. Now that period has become history, but history does have a strange habit of repeating itself. Everyone has their own pastime. I like rereading old books, looking at old photographs and imagining I have stepped back in history.

Valery Shchekoldin

I was born in the city of Gorky, on November 15th 1946. From the 1950s to 1980s I lived in Ulyanovsk, where I worked as constructor at an automobile plant after graduating from the polytechnic institute. At the age of 16 I began taking photographs, and in 1974 started work as a professional photographer. I was also photo correspondent for the newspaper Ulyanovsky Komsomolets. From 1975 I worked for Semya i shkola magazine.

In 1980 I moved to Moscow and lived a clandestine ‘basement’existence with no residence permit or registration, so I was unable to get a job. I hawked my photos round the editorial offices of newspapers and magazines, living on royalties whenever they were published. Only in 1995 did I get my long-awaited residence permit, by which time I was so fed up with Moscow that I no longer wanted to live or take photos there, although I still live in Moscow to this day. Just the same as 30 years ago, I have no permanent job. I only worked as a full-time member of staff once in my life, eighteen months for Kommersant when they first started, but I got bored and left. From 1995 to 1996 I was a correspondent for Stern magazine. Ironically enough, Paris Match awarded a prize for my pictures in Stern. In Germany I was given the art directors’ prize for magazine photos (1998), and for best photo (1999). I also received awards at the ‘Interfoto’ exhibitions in Moscow (1996, 1999).

Valery Schekoldin